The Front Range of the state of Colorado has experienced an extraordinary series of weather events this year. Over a few days in September 2013, heavy rains caused what the media dubbed “100-year flood” conditions across the greater Denver-Boulder area, saturated soils, and clogged streams with debris. Since then, the 2013-2014 winter has already secured a spot in the top five snowiest winters since 1938 according to snow-water equivalent (SWE) records from the University Camp Snotel site (elevation 10,300 feet adjacent to Niwot Ridge).

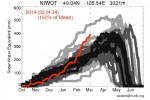

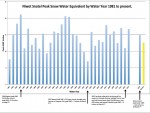

The Niwot Ridge Snotel site (elevation 9,910 feet) reports SWE values currently at 167 percent of median snow depth values. This is particularly impressive given that peak snowpack usually occurs around the 1 st of May; almost 40 percent of yearly snowpack falls in March and April. On the heels of the epic flooding in September—and with our snowiest months still ahead of us—what does this record setting year mean for winter research on Niwot Ridge, and the ensuing spring and summer months?

Extreme weather tests both our own (researcher’s) and our research design’s limits. With sites ranging in elevation from 7,200 to 12,500 feet in the Rocky Mountains, winter research at the Niwot Ridge (NWT) Long Term Ecological Research (LTER) site regularly tests these limits—with wind gusts over 100 mph and ground blizzards that reduce visibility to zero—but this winter’s extreme conditions have made this season exceptionally burly. Cold temperatures, deep snow, and mountainous wind drifts have stymied snow cats and buried snowmobiles. High wind speeds have turned ground blizzards into whiteouts that prevent researchers from finding tundra sites. Anemometers used to measure wind speed have been frozen into the snow; precipitation collectors have been buried entirely; and one graduate student searching for a lab on the tundra skiid right over its roof without realizing it.

Despite the weather, field technicians Hilary Buchanan and Vivian Underhill and graduate student Rory Cowie make the trek to remote NWT LTER field sites multiple times a week. Through a combination of motorized vehicles, skiing, post-holing, and endless shoveling, they collect weekly air and precipitation samples and an array of climate data. In many instances, collecting the data doesn’t mean just making it to the site; it also means creativity and improvisation in adapting instrumentation to this year’s conditions without compromising the research method’s integrity.

There is an upside to the record rains and high snowfall this year: as questions about global climate change become more pressing, extreme years like 2014 provide researchers a unique chance to investigate links between climate and ecology outside typical climatic ranges.

For example, LTER researchers study populations of American pika, a sensitive, high alpine species, because they could serve as a potential early warning sign for climate change. Increased snow cover at high elevations provides insulation and protection from the harsh conditions of the alpine, which could help the pika survive the crucial winter months. Conversely, high snow depths could stress pika populations further as lingering summer snow pack reduces their already short foraging season on the tundra.

Similarly, higher snow cover will bring increased water supply to moisture-limited dry alpine meadows—but shorten the growing season for many types of tundra vegetation. So while this winter has made logistics of research more difficult, it could make the results all the more valuable.

Pika and tundra vegetation are not the only organisms that inhabit Niwot Ridge and its surrounds. The Front Range Rockies are home to many human communities as well, from small mountain towns to the State Capitol on the plains below. What have these conditions meant for the “stress” on Front Range residents? Again, it could go either way. After September’s record rainfall, high winter SWE will continue to increase soil moisture. This will reduce water stress on forests, which in turn will reduce fire danger in the summer.

However, come spring, all the melt water from this high snowpack may have few places to go. With soils already saturated, reservoirs high, and streams choked with debris from the September floods, snowmelt could mean even more flooding for the Front Range—particularly if a rapid warm up or a rain-on-snow event occurs and melts snow suddenly and quickly . With this in mind, cleanup crews in Boulder and other municipal areas across the Front Range are prioritizing their efforts around culverts, bridges, and other areas prone to flood damage.

Years like 2014 are proof of why LTER research is so valuable. Some of Niwot’s climate records date back to the 1950s, and it is only when we reference these long-term records that we are able to fully appreciate the importance and implications of our current conditions. As we trend towards a potential record year for snowfall, NWT researchers are gearing up for the arduous task of recording a potential record snowmelt. Will it happen? We’ll just have to wait and see. For now, more snow is still being forecast.

Check out NWT’s Tundra Cam at http://instaar.colorado.edu/tundracam/view.php. Located on the Niwot Ridge next to the tundra lab at 11,500 feet, the interactive web cam can be controlled by anyone to pan around the tundra and observe the conditions up there.

Enlarge this image

Enlarge this image