This April, a Center for Limnology-led report in the journal PLOS ONE made waves in scientific circles. But the splash the massive new study of Midwestern lake water clarity trends made wasn’t because of its large dataset: it’s where that data came from that’s truly noteworthy.

In a study involving nearly a quarter of a million observations in 3,251 lakes spread across eight states and seven decades, the researchers themselves didn’t collect a single bit of data. Every observation came instead from a lakefront homeowner, boater, angler or other member of the public wanting to know a little more about what’s going on in “their” lake.

More and more, ecologists are looking at big picture issues but there aren’t enough scientists in the world to collect data for these projects, says Noah Lottig, a research scientist at the Center for Limnology’s Trout Lake Station and co-Principal Investigator of the North Temperate Lakes (NTL) Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) program. To get at data gathered before the LTER program began in the 1980’s, Lottig turned to a surprisingly prolific resource – citizen scientists. “There’s a lot of information out there,” Lottig says, “and, really, citizen data has been underutilized.”

In an attempt to capitalize on citizen-generated data, Lottig and a team of freshwater scientists from across the U.S. combed through state agency records and online databases full of water clarity measurements taken by lake associations and other citizen groups.

Previous studies have shown that citizen readings of Secchi disks—plain white, circular disks used to measure clarity in bodies of water—are nearly as accurate as professional scientists’ measurements, says Lottig. With a dataset covering more than 3,000 lakes and stretching back to the late 1930s, his team decided to ask questions about large-scale and long-term change.

What they found was that, on an individual scale, some lakes were getting clearer while others were not. However, says Lottig, combining all that data together indicates that there is a slightly increasing trend in water clarity at a regional scale. “Unfortunately,” he says, “the data don’t exist to explain those patterns.”

Though the citizen scientist dataset limited his ability to explain the patterns observed, Lottig says it suggests that such information can play a role in shaping future research — a possibility that has some scientific organizations taking notice.

“This study highlights the research opportunities that are possible using data collected by citizens engaged in making important environmental measurements,” says Elizabeth Blood, program director in the National Science Foundation’s Directorate for Biological Sciences, which funded the work. “Their efforts provide scientists with data at space and time scales not available by any other means.”

For Ken Fiske, it’s an effort that’s well been worth it. In 1985, Fiske saw a call for volunteers for a new Wisconsin citizen lake-monitoring program. Fiske, who had recently bought property on the shoreline of Lake Adelaide in northern Wisconsin, didn’t hesitate to sign up.

“My interest, initially, was in finding out what the quality of water in Lake Adelaide was and seeing what we could do to maintain it,” he says. “And if anything started to get out of whack, we could identify it very quickly.”

For the next several years, Fiske took a monthly five-hour drive up north to take measurements. Eventually, he got some neighbors to help. Nearly thirty years later, they are still going strong.

“It’s a cooperative thing and that’s what makes it work and we’ve been doing it long enough that it makes the results meaningful,” he says.

That meaning goes beyond the landowners around Lake Adelaide. All over the country, folks like Fiske have been peering into lakes for decades, collecting data on water clarity, temperature, and more. Now professional scientists are harnessing their efforts to try to answer some of the biggest questions on Earth.

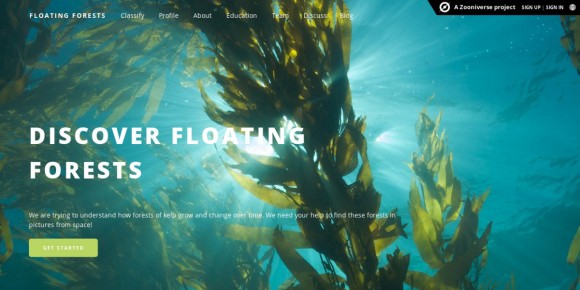

*You can read another example of professional scientists teaming up with citizen scientists to map out giant kelp forests in this issue of the newsletter.